Who is the forgotten man? Does anyone remember him today?

On January 17, 2021, President Donald Trump gave his First Inaugural Address. The theme of his speech was the triumph of the American people over the political establishment, special interests, and deep state bureaucracy that had grown thick in the swamps of Washington, DC. He said:

“What truly matters is not which party controls our government, but whether our government is controlled by the people. January 20th, 2017 will be remembered as the day the people became the rulers of this nation again. The forgotten men and women of our country, will be forgotten no longer.”

The rhetoric of the forgotten man goes back a long way. In his own First Inaugural, President Franklin D. Roosevelt laid out his plans to massively expand government power in the name of fighting the Great Depression. He said:

“These unhappy times call for the building of plans that rest upon the forgotten, the unorganized but the indispensable units of economic power, for plans like those of 1917 that build from the bottom up and not from the top down, that put their faith once more in the forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid.”

Author Amity Shlaes contends that FDR misused the term. She points to an essay by Yale professor William Graham Sumner in 1882 in which he said that the forgotten man is not the poor person who needs charity or government assistance, but the taxpayer whose wages are garnished to pay for such charity.

It is far too easy to win support for doing good works with other peoples’ money. “A government which robs Peter to pay Paul can always depend on the support of Paul,” said George Bernard Shaw, but it can also depend on anyone else not named Peter who wants to vicariously experience the virtue of generosity.

Peter, then, is the forgotten man, not Paul. Peter is the American taxpayer, the men and women who work just enough to support themselves and their families — not enough to buy lawmakers and lobbyists, but too much (or with too much pride) to fall into the welfare system.

Every time you hear Governor Brad Little boast about another historic and unprecedented investment in education, remember who is paying for it. As you watch a line of legislators argue on behalf of boosted bureaucratic budgets, remember the Idaho taxpayer whose hard-earned wages are going toward this or that program. Once you see government “investment” through that lens, it can really be infuriating the way our lawmakers talk about spending someone else’s money, then pat themselves on the back for their generosity.

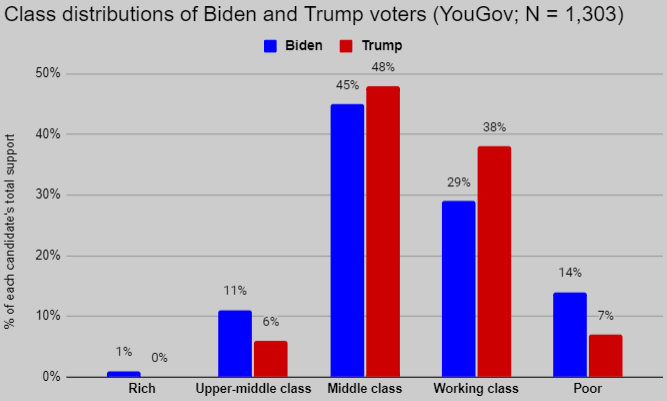

This eventually results in what is essentially an alliance of the top of society with the bottom against those in the middle. Millionaires and billionaires bankroll the Democratic Party, which promises handouts to those on the bottom rungs, paid for by those in the middle who vote Republican. This alliance is one of the lasting legacies of FDR’s New Deal.

I recently listened to the audiobook of Amity Shlaes’ The Forgotten Man: A New History of the Great Depression. It is well written, well researched, and easy to follow. She skewers the sacred cows that have come to graze in our popular conception of the Great Depression. You might have learned in high school history class that the Depression was caused by greedy bankers enriching themselves throughout the decadent 1920s, that President Herbert Hoover was too married to laissez-faire economics to do what needed to be done, and that FDR’s courageous expansion of government saved the American people and surely avoided a Fascist coup in our country.

Shlaes dismantles each of these myths one by one. The Depression had many causes, but bankers and industrialists were easy targets for an America eager to lay blame. Shlaes explains how the Roosevelt Administration spent years prosecuting former Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon on the most spurious charges because they needed a scapegoat for the ongoing failure of the New Deal. That sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

President Hoover was not the hands-off leader that popular histories like to portray. An engineer by trade, he saw the economy as a machine that could be fixed, and eagerly sought public/private partnerships. Construction of the Hoover Dam, a monument to American ingenuity, was initiated during his administration. Hoover tried all sorts of government programs, many of which were rolled into the first phase of the New Deal after FDR took over.

Herbert Hoover and his predecessor, Calvin Coolidge, represented the same Republican dichotomy we see today: The progressive reformer versus the small government zealot; one who wants to use government and the other who wants it to stay out of the way; one who believes government can help people, and the other who understands that government help inexorably diminishes personal liberty.

Whereas Hoover believed the government had a responsibility to manage the economy and to fix it if it went awry, Coolidge and his own predecessor Warren Harding believed that was beyond their constitutional purview. When America went into a post-World War I depression in 1920, President Harding slashed the federal budget, cut taxes, and let the economy figure itself out. By 1923, unemployment was at 2.4% and America was well on its way to the prosperity of the Roaring 20s.

By 1933, FDR promised a new deal for the American people, one based on Keynesian government spending, regulatory experimentation, and what President Obama’s Chief of Staff Rahm Emmanuel would later call not letting a crisis go to waste. Just as Covid-19 provided cover for all sorts of totalitarian regulation and pharmaceutical experimentation that was years in the making, so too did the Depression give progressive activists room to implement the quasi-socialist policies they had long desired.

Franklin Roosevelt’s First Inaugural struck a similar tone to the Emperor in Star Wars, who “reluctantly” accepted emergency powers to deal with a crisis:

“It is to be hoped that the normal balance of executive and legislative authority may be wholly adequate to meet the unprecedented task before us. But it may be that an unprecedented demand and need for undelayed action may call for temporary departure from that normal balance of public procedure.

“I am prepared under my constitutional duty to recommend the measures that a stricken nation in the midst of a stricken world may require. These measures, or such other measures as the Congress may build out of its experience and wisdom, I shall seek, within my constitutional authority, to bring to speedy adoption.

“But in the event that the Congress shall fail to take one of these two courses, and in the event that the national emergency is still critical, I shall not evade the clear course of duty that will then confront me. I shall ask the Congress for the one remaining instrument to meet the crisis--broad Executive power to wage a war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.”

Shlaes describes the draconian efforts of the Roosevelt Administration to wrest control of the economy away from the American people:

The National Recovery Administration (NRA) set price floors and ceilings, paid farmers to destroy crops and livestock in a time when families were starving, and even attempted to jail a family of Jewish immigrants who sold chickens in Brooklyn because their establishment violated NRA rules.

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) destroyed private investment in the hydroelectric market and set a precedent that government should control power distribution.

The Social Security Act (SSA) created a government pension system funded by taxing the working man.

The Works Progress Administration (WPA) hired otherwise unemployed workers, including writers and photographers who were tasked with creating propaganda about the New Deal itself.

On of the most pernicious effects of the FDR presidency was the way in which he created patronage relationships between the government and voters. The New Deal established the precedent that the federal government has a mandate to take care of individual Americans, and many components of the program — such as the WPA — explicitly allocated money to favored groups. FDR used federal largess to create loyal constituencies among groups such as women and blacks, the latter of whom began voting majority Democrat for the first time since the Civil War.

Shlaes convincingly explains that the New Deal, rather than fixing the Depression, actually prolonged it. We were not fully out of the woods until well into World War II. Unfortunately, the American people responded favorably to a government that appeared to “do something” — despite the Depression getting even worse in 1936, the American people reelected FDR in a massive landslide, and then gave him two unprecedented terms after that. Because of this, government action is now the norm, and we will never again have a leader like Harding who responds to economic turmoil by cutting taxes and staying out of the way. Barack Obama’s American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 and Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 both followed the pattern of the New Deal in that they massively expanded government, siphoned money to Democrat-friendly industries, and were — if anything — detrimental to the economic crises for which they were ostensibly passed. “Never let a serious crisis go to waste” indeed.

We moderns tend to have short attention spans. Events which once dominated the news cycle for weeks or months in the past now come and go within days, or even hours. The Bush and Obama Administrations are ancient history for most people, while the 1930s and 40s might as well be myth. It is easy to forget that our country’s love affair with central planning has been going on for nearly a century. One of the most striking figures from the New Deal era is Henry Wallace, FDR’s vice president from 1941-45. Prior to that he had been Roosevelt’s Secretary of Agriculture, and had greatly expanded what was once a small department into one that was active — and expensive. In 1942, Vice President Wallace delivered a speech declaring “the century of the common man,” casting the fight against Nazism as the culmination of two centuries of revolution by the common people. In doing so, he lumped the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 with the American Revolution of 1776 as parts of the same great crusade.

Now, perhaps one can forgive such rhetoric as being necessary when we were allied with Stalin and the Soviet Union against the greater threat of Hitler and Nazi Germany. However, the entire tone of Wallace’s speech suggests that he admired the Communists, and generally supported their aims. Wallace’s “common man” was not the quintessential American worker, the rugged individualist who supported his family and cherished liberty, but the socialist idea of oppressed workers rising up and seizing the means of production. Like Roosevelt, he forgot the forgotten man.

Incidentally, Wallace’s speech inspired composer Aaron Copland’s excellent Fanfare for the Common Man.

Conservative Democrats so feared Wallace’s sympathies that they fought hard to have him replaced on the 1944 Democratic ticket by Senator Harry Truman of Missouri. Imagine if Wallace had succeeded to the presidency in April 1945 instead of Truman. How differently might history have played out? Wallace challenged Truman from the left in 1948, running for president on a progressive platform, accepting the endorsement of the American Communist Party in the process. (His running mate was the idiosyncratic Senator Glen Taylor of Idaho, who probably deserves an entire post himself.)

Conrad Black wrote a good overview of the man for National Review ten years ago. Wallace’s rhetoric is a perfect example of the top and bottom versus the middle. He wanted to create a government powerful enough to micromanage every social and economic interaction to bring about equality and prosperity, building it on the backs of the forgotten men who simply wanted to support their families.

As you can see, leftist rhetoric has changed little in the past century. Remember that whenever leftists accuse you of having “backward” views: their own policies are based on 19th century ideas that have failed everywhere they have been tried. That is why Wallace’s tenure and rhetoric is so striking to me. It is easy to assume that socialism and big government are relatively new things in American discourse, yet here was a sitting vice president advocating for socialist revolution, who was part of a presidential administration that had already massively expanded government into all areas of society.

In many ways, the story of the fight for freedom in America has been a very long defeat. No Republican administration since FDR, not even Reagan or Trump, was able to undo the New Deal. On the other hand, Democratic administrations under Lyndon Johnson and Barack Obama built on Roosevelt’s foundation, expanding government even further.

In fact, Republicans often internalize the previous generation’s progressive victories as their own. Who today in the GOP outside of perhaps Senator Rand Paul even dares to suggest rolling back Social Security or Medicare? Republicans in the 1950s could not dismantle the New Deal, they couldn’t undo the Great Society in the 80s, and they failed to repeal Obamacare when they controlled both houses of Congress and the White House in 2017.

Republicans are just as guilty as Democrats with regards to the forgotten men and women of America. They often adopt the perspective that government action is necessary to take care of people, perhaps hoping to steal the left’s thunder. At the other end, until Trump, Republicans often derided America’s working class, not caring about their livelihoods so long as GDP continued to rise.

Even so, our fight is not in vain. Soberly confronting the magnitude of our battle means reorienting our perspective. We must denounce not only the leftist idea that the purpose of government is to take care of people, but also the neoconservative idea that working class communities are not worth attention. We must rediscover the forgotten man.

Who is the forgotten man today? Is it the schoolteacher, the policemen and first responders, the military personnel, or the front line doctors and nurses? I don’t think so. As valuable as all these people are to society, none have been forgotten, have they? All of them enjoy support from the government and the people, though perhaps not as much as they might want.

No, the forgotten man remains the taxpayer, the regular working men and women who go to regular jobs doing regular things, who make enough money to stay off welfare but not enough to matter to the political establishment. They are the ones who are continually asked to give more, for whom inflation continues to eat away at any chance of building their own investments, who will be lucky to retire, much less give an inheritance to their children.

For a brief, fleeting moment, the forgotten men and women of America made their voices heard. They voted for an outsider who promised to return to them control of that government which Abraham Lincoln called of the people, by the people, for the people. Yet America today is more totalitarian than ever. Dissidents are being persecuted and imprisoned, discourse is being censored, and our policymakers — elected and otherwise — salivate at the thought of returning to Covid-19 lockdown restrictions.

Restoring America to its small government heritage requires both big ideas and steady, incremental work. We must not be afraid of going after big entrenched programs such as Social Security and Medicaid, but we must also engage in the boring, grueling work of winning the small battles as well. The next time Gov. Little proposes a free college plan, call your legislators and urge them to defeat it. Pay attention to the budgets that JFAC considers each year, how they appropriate billions of your dollars to state agencies that continually increase their scope and influence. Push back on public school curricula that casts government as a loving protector and savior to the American people.

Perhaps the most unfortunate consequence of the New Deal is in how Republicans accept the premise that government is destined to grow indefinitely. I suggest that it doesn’t have to be this way. I know there are people out there, voters and potential candidates, who truly have a vision for reducing the size and scope of government, for creating a new society based on individual liberty, not government largess. This task is not impossible, rather it is necessary, for the sake of all the forgotten men and women of America.